Mentoring is a fundamental activity in education and research, one of the key mechanisms for training the next generation of researchers and nurturing excellence.

Mentoring Matters

Mentorship is the core of the collegiality and collaboration required for high-quality research. The qualitative report on workshops conducted by Wellcome Trust (Helene Moran and Lucy Wild, (opens in a new window)Research Culture: Qualitative Report, 2019) indicated that mentoring practice has a significant influence on perceptions of research culture and prospects for a research career.

In our UCD Research Culture Survey and subsequent World Café feedback discussions, access to quality mentorship was deemed uneven across the university. In response to the free-text questions in the survey, many respondents identified mentoring as one of the practical things that the University could do to promote a positive Research Culture. For example: “Formalised peer mentoring for recently appointed faculty” and “a structured mentorship programme may be useful, e.g. making it explicitly clear to senior academics steps they can take to help early stage researchers”.

Often, the first thing that comes to mind when thinking about mentoring relationships in a university, is the dynamic between a supervisor and a doctoral researcher. Certainly, a positive experience of mentoring during the doctoral phase of a research career can have significant benefits that last throughout a researcher’s working life. Good mentorship is a perpetuating cycle. Those who have benefited from positive mentorship confer those qualities to those they themselves mentor, creating, as Elva Johnston put it, ‘intergenerational support networks’ which are valuable for both research and research careers. This method has been the standard for nurturing mentoring skills in the past and demonstrates that the same skills can be taught through more formal training modules, helping to ensure that good mentorship is not a matter of luck but a reasonable expectation in a research career at UCD.

While the majority of the suggestions for mentoring were aimed at early-stage or junior researchers, there was also a desire to see “more mentoring programmes for all levels”. To learn more about good mentorship practice at UCD and add to the Research Culture Initiative toolkit of resources, we talked to members of the research community about membership. Several of those we interviewed have been recognized for their excellence as mentors. The role of the mentor can be varied, but three common points of best practice were raised by those interviewed.

Facilitating Professional and Personal Development

A good mentor invests in the mentee as a person, helping to develop their outlook as a colleague and collaborator. Every mentee is different so it is best practice to get to know each individual to understand how best to offer support. This is an essential type of caring that underpins the most effective mentoring relationships. One of the rewards of being a mentor that Cormac Taylor identifies is helping someone develop as a person and build not only a career, but a life.

Creating a Safe Space

Creating a space where people can try, flounder, and try again is fundamental to the research process. In Project Aristotle ((opens in a new window)Google, Re:work Guide: Understand team effectiveness), Google identified Psychological Safety or the security to take risks and be vulnerable in front of colleagues as one of the five decisive qualities of highly effective teams. Good mentors support their students and junior colleagues through the full practice of research from failed attempts to success.

Listen

Researchers are trained to think critically and disseminate scholarship, so while it may be antithetical to standard practice, experienced mentors advise listening instead. Let the mentee talk. For the most part, they know what they need to or want to do; they just need the opportunity to talk it through. As Pat Guiry observes, ‘Can’t beat a cup of coffee and sitting down with someone.’

Mentoring for All Career Stages

More and more it is recognised that good mentorship is essential at all stages of a research career and for all members of the research community. Good mentorship is important for research managers, too. An external perspective can help frame the scope of work and offer practical advice on negotiating the network of relationships involved in managing a research project. Mentoring does not necessarily need to be a hierarchical experience as between a senior researcher and more junior colleagues or students. Good mentoring can also be shared through peers. Katie Whelan gives us a good example of positive peer mentoring among her fellow doctoral candidates. Peer mentoring is also a model for researchers at senior levels of their careers.

Mentorship is an act of collegiality and collaboration. For many members of the research community, mentoring is the first experience of this positive aspect of research culture. Respect is embedded in the foundation of collegiality. Good mentors view the opportunity to support the development of another researcher as a privilege and honour.

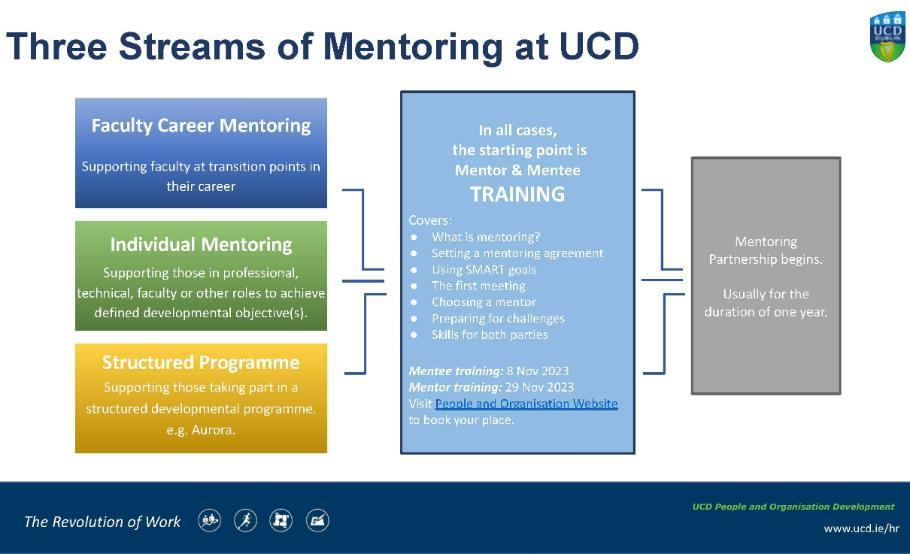

More UCD Resources for Mentoring

For more information, visit the UCD Mentoring webpage on the People and Organisation Development website.