Tuesday, 27 January, 2026

Researchers: Assistant Professor Alexander Kondakov, Sergey Katsuba

Summary

Research by Dr Alexander Kondakov, Sergey Katsuba and colleagues has provided the most reliable data on anti-LGBTQ hate crimes in Russia, where such crimes are not reported in official statistics. Their work developed alternative methods of calculating hate crime incidents, regardless of the willingness of law enforcement to record these crimes.

The project has shown evidence of the influence of discriminatory state policies on the level of violence against marginalised communities. By bringing to light stories of LGBTQ people in Russia, and providing insight into the reality of oppression and violence, the project helps advocacy groups to campaign for change, and it enables future generations to know what it is like to live in conditions where violence against a particular group is normalised.

Research description

In 2013, Russia enacted the so-called “gay propaganda” law – a censorship legislation banning LGBTQ-related content from circulation and LGBTQ activists from organising public events. This discriminatory legal act increased levels of prejudice and deeply affected the LGBTQ community. The Russian authorities do not recognise homophobic hate crimes and do not monitor them. Research by Dr Alexander Kondakov, Sergey Katsuba and colleagues used online public databases of court rulings to find cases of violence against LGBTQ people and generate statistics on them. The data that were generated by the project are the only reliable data on such violence, and the method is applied on a continuous basis.

The research project has established that homophobic violence is on the rise in Russia after the “gay propaganda” law. Between 2010 and 2020 the research managed to identify 1056 hate crimes committed against 853 individuals, with 365 fatalities. The number of crimes after the “gay propaganda” law was enacted is three times higher than before.

These findings are being shared through academic articles, citations by global and national news agencies, cooperation with international organisations, international conferences and workshops, art, and a designated website.

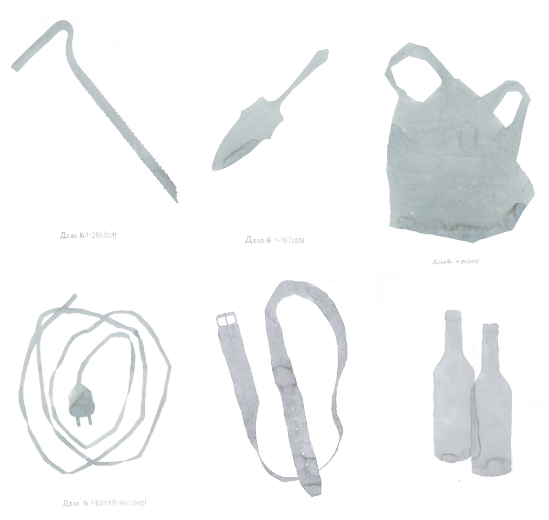

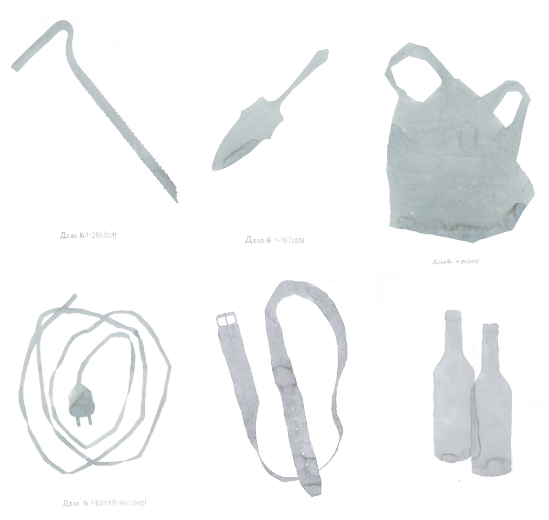

For example, in 2022 the project contributed to the international effort to monitor hate crimes by submitting a report to the Organization for Security and Co-operation in Europe (OSCE). The OSCE used the project team’s data in their most recent annual report, and on (opens in a new window)their website which contains a database of hate crime cases, publicising the statistics and the stories of the victims. (opens in a new window)An art exhibition, informed by the research, and depicting murder weapons from the analysed cases, travelled from St. Petersburg to Moscow and to Berlin, and is open to other locations (adjacent image by artist Polina Zaslavskaya).

Research impact

Political impact

The project has affected the way people see hate crimes against LGBTQ people in Russia. It is understood not as a series of isolated crimes but as a systematic problem; a product of state-sponsored, institutionalised homophobia. Year after year, the research has provided more insights into the reality of this system and the everyday violence against LGBTQ people that it produces. These hate crime cases are not reported by the media and are neglected by the authorities.

Russia’s current government is reluctant to introduce legal changes based on the human rights and anti-discrimination efforts. Moreover, the government actively represses any voice of dissent or civic engagement. LGBTQ organisations and individual activists have been forced to shut down and flee. However, the data on hate crime generated by the project helps to keep the record of anti-queer violence instigated by both the government’s direct involvement and by its inaction. The project’s findings are used by the Russian LGBTQ organisations in exile (including organisations in (opens in a new window)Perm and (opens in a new window)St. Petersburg) to advocate for change. The results of the study have also been used by wider international advocates for human rights and by the media (see Links and References below for examples).

The law banning “gay propaganda” in Russia was introduced in 2013 as a measure to limit public access to information on LGBTQ topics. It was defended by Russian politicians of the highest positions – including Russian dictator Vladmir Putin – as a simple measure which did not harm actual LGBTQ people, but only targeted information. This research proved with rising numbers of anti-LGBTQ crime that the “gay propaganda” law was an instance of political homophobia and as such it greatly contributed to the growing death toll of LGBTQ folks. In 2022, Russia amended the “gay propaganda” law with even more draconian measures. With the ongoing war and continuous crackdown on civil liberties, the Russian government confirmed its departure from the values of human life, respect of individual autonomy and basic principles of democracy.

Social and cultural impact

The research generated a database of hundreds of narratives about criminal incidents involving LGBTQ victims. Even though all these narratives are sourced from criminal court rulings and are, therefore, mediated by the institution of criminal justice, they tell the stories of actual people targeted by perpetrators of violence for their sexuality.

Hence, the research brought to light stories of LGBTQ folks in Russia and provided an insight into the reality of oppression and violence, as well as everyday joys and simple pleasures. These stories have been (opens in a new window)widely shared across many channels, from (opens in a new window)art exhibitions to (opens in a new window)Russian media to international reports (see additional examples under Links and References below). The project raised awareness of LGBTQ Russians as victims of senseless violence who are additionally vulnerable due to the lack of protection from the police.

Together, these stories challenge our understanding of social relationships centered on queer sexualities by adding complexity and sophistication to sometimes overly simplistic pictures of homophobic environments. This, in turn, helps us to imagine societies without violence, even if such societal imaginations are only utopias.

Academic impact

The research generated unique data on criminal cases of anti-LGBTQ violence between 2010-2020 in Russia. There is no comparable database of this size and reliability. The study also contributed to both methodological and theoretical academic discussions. In terms of method, the research proposed a new way of reading criminal court documents as reflections of hidden social practices (sexual activities and violence). As for theoretical contributions, a thorough analysis of hundreds of cases of violence against LGBTQ people showed how political manipulation with people’s emotions leads to violence against historically disadvantaged communities.