David Musa-Aboki

Tempelhofer Feld Berlin's Urban Green Pearl

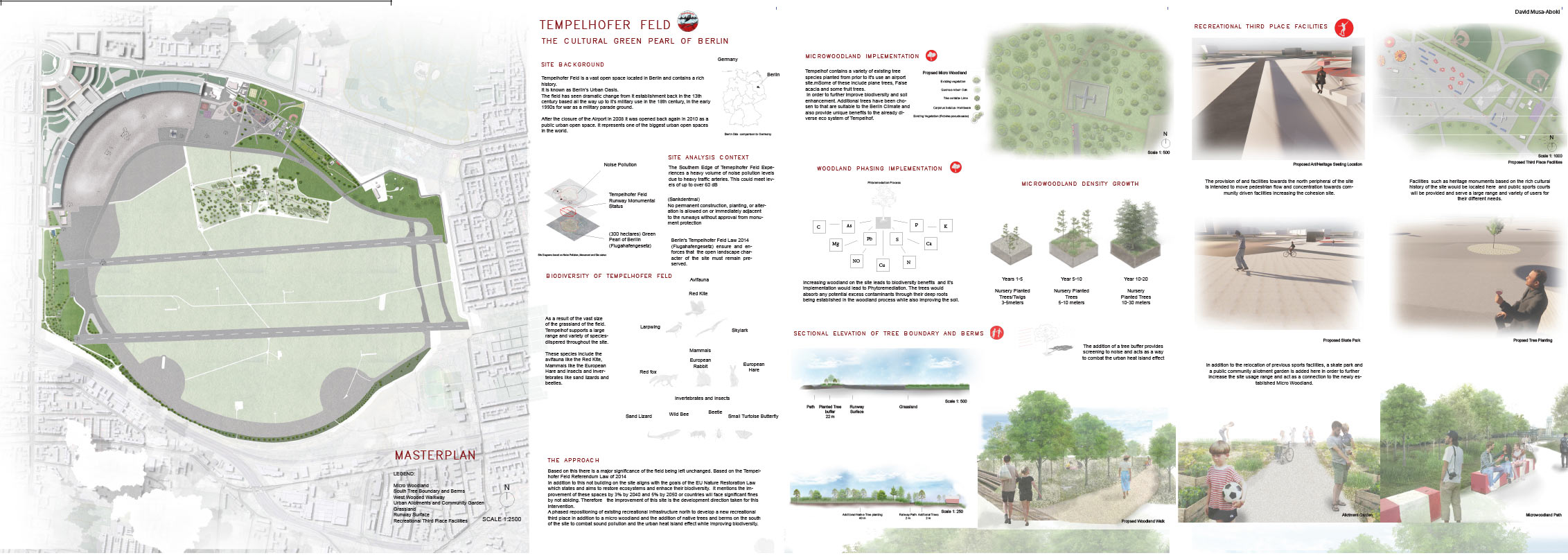

As Berlin grapples with rapid urban growth and the accelerating impacts of climate change, Tempelhofer Feld stands at the crossroads of this, however with thoughtful ecological and social interventions like the introduction of micro woodlands, biodiversity zones, and convenient accessible recreational spaces the field can enhance its biodiversity, support climate resilience, and protect its unique character as a public space, ensuring it remains a model of inclusive and sustainable urban nature.

One of the most promising ecological interventions is the creation of micro woodlands. Drawing inspiration from the Miyawaki method, microforests are dense, fast-growing patches of native vegetation that replicate the structure of natural forests in miniature form (Scott & Lennon, 2016). These woodlands are not only incredibly effective at sequestering carbon pollutants and improving air quality, but they also help cool surrounding areas, offering significant relief from the urban heat island effect. Cities like Paris, Brussels, and London include microforests and have already proven their worth, like the Petite Ceinture or the London Design Biennale. (Scotscape, 2020) Revitalising small spaces while attracting a diversity of wildlife. The introduction of a micro woodland location at Tempelhofer Feld could provide shaded zones, create additional habitats for insects and birds, and boost the site’s overall ecological resilience without overwhelming the core essence of openness.

Another intervention that could blend even more subtly into the landscape is the creation of tree berms and natural shelters. Tree berms are gently raised mounds planted with shrubs and small trees, designed to act as windbreaks, shaded resting areas, and microclimate regulators. Because they can be shaped organically, tree berms would not disrupt the vast, open feel that Berliners prize at Tempelhofer Feld. Strategically placed southern berms could also protect sensitive zones from overexposure to human traffic, subtly guiding movement across the site without the need for intrusive barriers.

Building on the concept of the "third place" — neutral spaces where community life flourishes outside of home and work (Oldenburg & Brissett, 1982) — there is strong potential to add low-impact recreational zones along the northeast of the field’s edges. A Small skatepark, shaded picnic lawns, and community gardens repositioning could provide needed gathering places without fragmenting the core central open space. These third places would foster greater social mixing, encourage outdoor activity, and offer spaces for cultural expression while relieving some of the pressure on the central and southern parts of the field, giving nature more room to thrive undisturbed.

What all these interventions have in common is that they work with, not against, Tempelhofer Feld’s unique identity. They offer a vision of a living landscape where the one where the existing trees, birds, insects, and humans can all find a place, and where the field’s rare openness is enhanced rather than diminished and taken for granted.