The breadth of the EU’s environmental rules is now considerable, and EU law affects virtually every facet of environmental regulation. However poor compliance levels continue to plague the effectiveness of the EU’s environmental policy and, in many cases, important environmental rules are ignored in practice. This may be unsurprising: policing the enforcement of environmental rules, applicable throughout the entire territory of the EU, poses severe and particular resource challenges for traditional State-led enforcement.

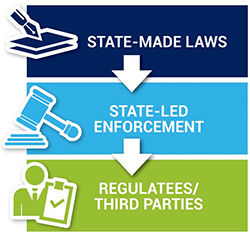

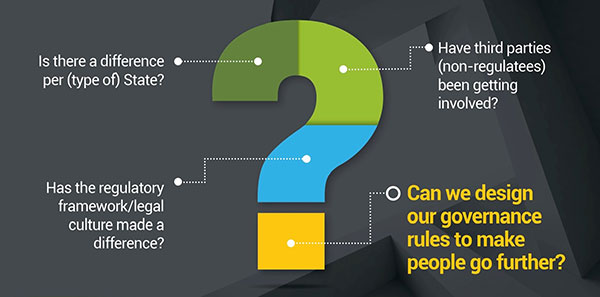

At EU level, this problem is compounded by the difficulties in securing political agreement on stronger supranational enforcement measures, such as an EU environmental enforcement agency or binding generally applicable EU rules on inspections and enforcement. Since the 1990s, the EU has recognised these challenges by strongly promoting non-hierarchical methods of environmental governance, including decentralised, non-State-led enforcement of environmental law. More broadly, the movement towards non-hierarchical enforcement ties in with the ongoing debate about the need for a greater emphasis on environmental democracy, environmental justice and human rights.

In Europe, the legal move towards decentralised enforcement is epitomised by the ground-breaking 1998 Aarhus Convention on access to information, public participation and access to justice in environmental matters and ensuing multiple legal instruments enacted at EU and national levels to implement this Convention. The far-reaching effects of these new environmental governance laws are currently being played out before EU and national courts.