Mountain Landscapes from the eyes of a Quaternary Geologist

The view down Fraughan Rock Glen into the Glenmalure Valley, both the glen and larger valley, are the result of glacial erosion.

By Sam Kelley, Assistant Professor of Quaternary Geology, School of Earth Sciences, University College Dublin.

In recognition of International Mountain Day, Dec. 11th, where we observe mountain regions’ role in society and their importance to our planet, below is the first in a series of blog posts that highlight interdisciplinary perspectives on Mountain Landscapes found within the UCD Mountain Research Group.

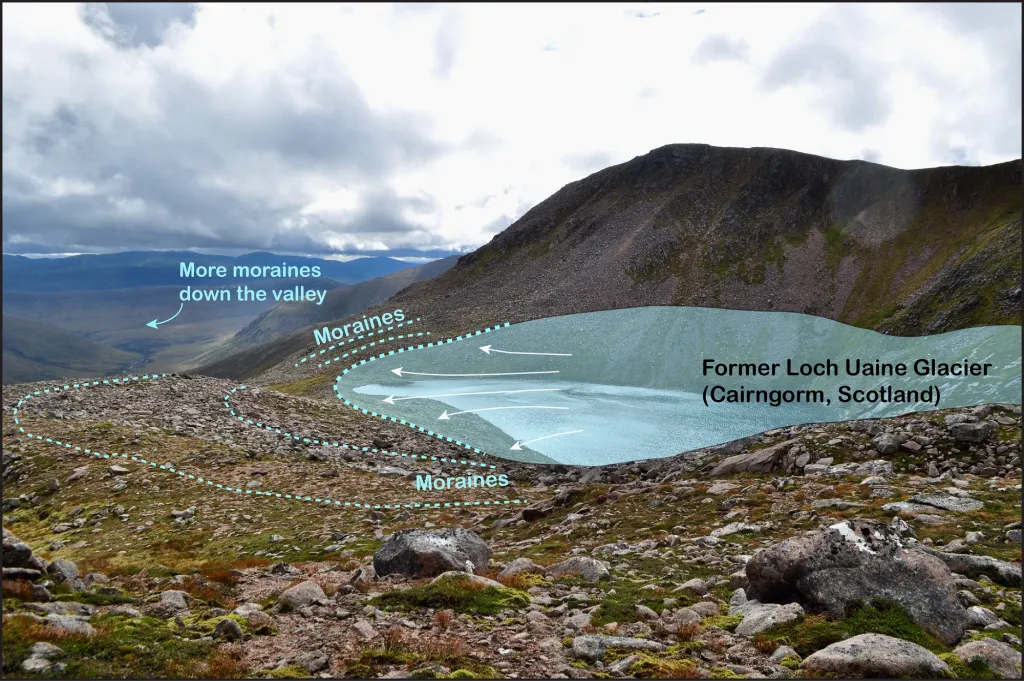

Mountain landscapes contain a wealth of geologic information. The insights gained from geologic mountain research ranges from understanding how continents collided millions of years ago to revealing how climate drove the expansion and recession of ice sheets and glaciers from hundreds of years ago to hundreds of thousands of years ago. In total, these geologic forces have shaped many of the mountain landscapes we are most familiar with. As a Quaternary geologist, my research in the mountains focuses on unravelling connections between past ice masses and past changes in climate. Mountain glaciers are sensitive to small changes in climate, receding into the high corries as the temperature warmed and expanding down the valleys when the climate cooled. This expansion and contraction of glaciers leave a mark on the landscape in the form of moraines, which mark the extent of a glacier at some point in the past.

This photo shows the extent of a former glacier located in the high in the Cairngorm of central Scotland. The light blue shaded area shows the smallest extent of the glacier before it melted away (arrows indicate the direction of ice flow). The blue dotted lines show the location of moraines, which mark the extent of the glacier at different points in time.

To solve the glacial puzzle of where were the last bits of ice occurred and when they finally melted, I create maps of moraines to reconstruct the extent of past glaciers. As each moraine marks the extent of a past glacier at one point in time, sets of moraines record how the glacier changed in size through time. Then to determine when the glacier extended to each of these moraines, I use a technique called surface exposure dating, which determines how long a rock surface has sat on the landscape since the thick glacial ice covering it has melted. It’s a bit like measuring a rock’s sunburn, but rather than exposure to radiation from the sun, we’re collecting rock samples to determine how long they have been exposed to radiation from supernovae in space (much less harmful radiation than that from the sun). By measuring isotopes in the rocks, I can determine how much time has passed since the glacier receded off the landscape. See blog at this link for more information about surface exposure dating: (opens in a new window)http://www.antarcticglaciers.org/glacial-geology/dating-glacial-sediments-2/cosmogenic_nuclide_datin/.

A UCD research team collecting samples for surface exposure dating. These rock samples will undergo processing at the UCD School of Earth Sciences in Dublin.

The combination of glacial landforms, and the rocks and sediments they contain, hold information about how mountain landscapes have changed in the past, on time scales that are much longer than human observations. Through the collection of numerous rock samples from sets of moraines, we can reconstruct how glaciers in mountain landscapes changed in response to past climate change. This information is valuable, as it tells us how past climate change was expressed in these mountain landscapes, providing context for the ongoing changes we observe in mountain landscapes today.

The view down Fraughan Rock Glen into the Glenmalure Valley, both the glen and larger valley, are the result of glacial erosion.

To view mountain landscapes in Ireland that are formed by past glaciers, visit the Irish Ice Age Trail: (opens in a new window)https://sites.google.com/view/irishiceagetrail