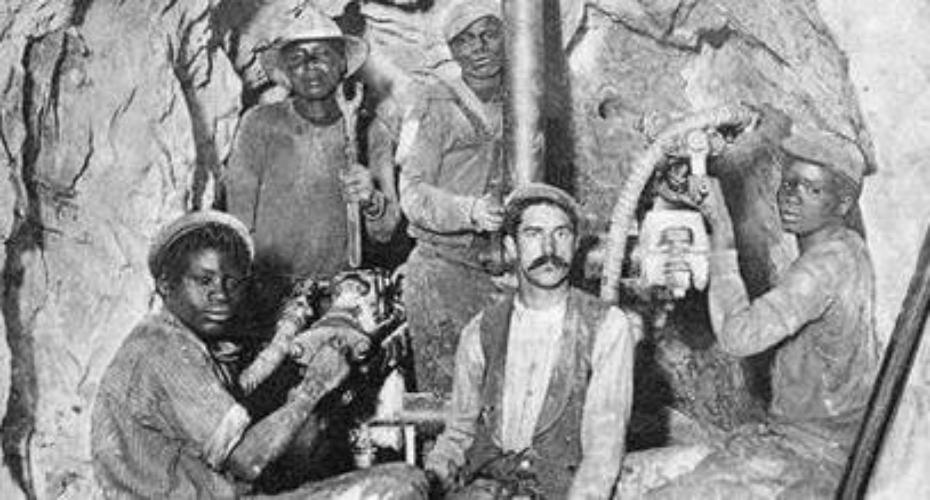

Cape Town slaves to migrant gold miners - a colonial continuum in South Africa?

Thursday, 20 July, 2023

Dr Linda Mbeki, a postdoctoral fellow at the University of Pretoria in South Africa and an assistant curator at Iziko Museums of South Africa, is in Dublin this summer on the UCD Discovery Visiting Global Fellowship Programme. Linda’s research focuses on migration and diet of enslaved people at the colonial Cape, and workers’ migration to the gold and diamond mines during South Africa’s mineral revolution. Her UCD host is Dr Robin Feeney, a lecturer in Human Anatomy at UCD School of Medicine.

The food you eat, the places where you live - your bones and teeth record your life.

Dr Linda Mbeki uses isotopic analysis to determine population movements and diets from chemical signatures in the bones and teeth of human remains from the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries.

She is investigating the progression from enslavement in Cape Town to indenture and ultimately to migrant labour as migration underpinned the South African economy.

South Africa was officially colonised in 1652 by the Dutch and slavery was the mainstay of the labour force for almost two hundred years. The Cape colony remained under Dutch rule until 1795 before it fell to the British, before reverting back to Dutch Rule in 1803 and again to British occupation in 1806. Together with colleagues from the Netherlands, Linda’s ground-breaking work has already shown that enslaved people on the Cape - who were presumed to have survived on a diet of seafood - did not even have access to this.

“ So you have to wonder if they're not eating an abundant and cheap form of protein, what are they eating? And it turned out that they relied on plants to get their protein. I thought the cheapest thing that they would eat was fish, but actually they had to go cheaper. ”

Her analysis of the mine records from the following century showed a more varied diet than that eaten by enslaved persons. The archives suggest this was likely about maximising the men’s productivity. Further evaluation of the archival data suggests that although a varied diet was “available” to miners, illnesses associated with inadequate food and poor living conditions were responsible for the high mortality.

Linda is combining her lab work on the bones with archival research to build a picture of what life was like for marginalised people at the time. She describes the disparity in how black and white miners were treated in the years preceding the advent of apartheid.

“Working conditions were terrible. There was one mine where there was a complaint that the black workers had to go down for up to 16 hours, and there was no water or food brought to them. And they made a point to say that the white miners could go to work an hour later and they were given food and they took a two-hour lunch break. So there were very different conditions for black and white miners.”

Her UCD host Dr Robin Feeney has a longstanding collaboration with colleagues in South Africa, which is how she made the connection with Linda.

“Mostly Sefako Makgatho Health Sciences University and University of Pretoria. We’re in a large consortium grant called Dirisana+ and through that we are able to support some of Linda’s research.”

Robin explains how the UCD Discovery Visiting Global Fellowship Programme is also helping Linda to progress her work.

“ It has clear professional and personal benefits to everyone involved, not just the visiting researcher. And the ability to have a few thousand extra euros to allow somebody to come to Dublin, to be able to access lab facilities, learn new methods, collect data, analyse data - that all helps towards getting the job done. But it’s equally valuable for the mentorship and for expanding outside of your field of view of how you see your project going. I know since Linda has come here lots of people have been very interested in her project and she can see how it can be expanded into ten years’ worth of research. ”

Linda agrees.

“I have to thank the Institute for Discovery and I have to thank the Humanities Institute because they also made a contribution to my research.”

Linda will now be involved in a two-year multidisciplinary Humanities Institute project about extractive economies.

“I had never even heard the term until I met Humanities Institute director Anne Fuchs. It’s nice to know, as Robin said, that you can fit in places that you never would have thought you could. That’s really been a wonderful development.”

Linda’s work - which merges chemistry, biology, history and culture - examines life over 100 years ago, but it has “big implications for today”, says Robin.

“This is still happening in South Africa. Illegal miners are down there for ten, twelve hours a day or three, four days at a time. They get lost and they don’t come back up.”

Although her research is “intellectually very stimulating”, Linda finds it “distressing” to think of the human cost of colonial forced migration, enslavement and hard labour.

I think there’s a strong case for reparations.”

Listen to the (opens in a new window)podcast