The substance of the left-right dimension in Ireland

Author: Thomas Däubler

Date: 21 September 2021

Empirical analyses of party competition typically take one of two broad approaches towards estimating left-right positions. Either they start from theoretical considerations regarding the content of this dimension and derive measurement rules from those – the deductive approach – or they infer such a dimension from raw data (e.g., covering the content of election manifestos) with some kind of statistical technique – the inductive approach. Advantages and disadvantages of doing it either way have been discussed for a long time, but the debate has mainly focused on questions of measurement validity. It has largely been overlooked that inductive approaches – treating left-right as a “superdimension” that best explains observed differences in textual or behavioural data – allows us to learn more about the content of the main axis of political competition. This is the core point of a (opens in a new window)new paper published in Party Politics (open access) with Kenneth Benoit.

Answering the question of what left and right “really means” can be tricky. Ireland illustrates these difficulties – with regard to party competition, it has often been considered as the “odd one out”. Political competition in Ireland has traditionally been linked to the Civil War cleavage rather than to issues dominating politics elsewhere. However, these days, how different is party competition in Ireland from other developed democracies?

We can answer this question with data from the long-standing international (opens in a new window)Manifesto Project. The collection of the data follows a classic content analysis approach. A coder parses an election manifesto into statements and annotates each statement with a category from a predefined coding scheme. This gives us information about the coverage of 56 different policy categories – but not yet a left-right position. In the paper, we use a Bayesian negative-binomial variant of the (opens in a new window)“wordfish” model that Slapin and Proksch first developed for use with word frequency matrices. This allows us to infer a latent variable that best explains the observed relative category usage patterns, and we interpret this dimension as “left-right”.

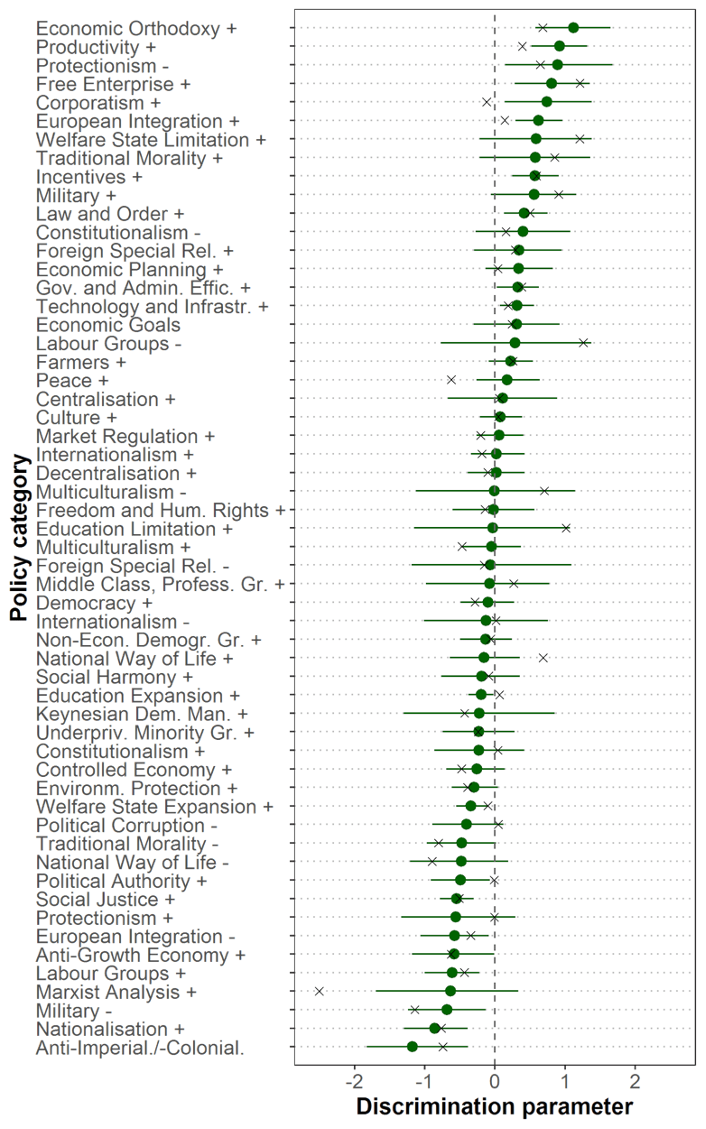

Here, we apply the model to Irish manifestos from the elections between 1992 and 2016 (data for 2020 are not yet available). Figure 1 shows the results for the so-called discrimination parameters. They show the contribution of each category to the left-right dimension, with positive values corresponding to right and negative ones to left items (the value of zero reflects the “average” category). From top to bottom, the policy categories are sorted from right to left.

We can see that the most “rightist” items relate to free-market policies such as positive references to economic orthodoxy and to productivity or negative statements about protectionism. At the other end of the scale, we can not only find socio-economic policies (such as positive statements on nationalization, Marxism or labour groups) but also “anti-imperialism” (whoever the culprits may be) and negative statements about the military. Interestingly, divisions over European integration also contribute quite strongly to the super-issue on both the left and the right side.

Figure 1: Contributions of the policy categories to the left-right dimension (Ireland, 1992-2016)

Note: Shown are posterior means and 95% Bayesian confidence intervals. Crosses show posterior means for the international set of documents. In the category labels, + represents positive and – negative statements.

We can also compare the results to those for a wider sample of countries in a similar period, as covered in the paper. The mean discrimination parameters from that analysis are shown as crosses. To begin with, the nature of political competition in Ireland is not so different after all. The rank correlation of the means reaches a value of Spearman’s rho = .74. Looking at the categories with the biggest differences reveals a few interesting patterns. No one seems to quarrel about limiting education expenses in Ireland, while negative references to labour groups are also not divisive. Ireland is also different in the sense that positive references to a “national way of life” or negative statements about multiculturalism do not play a polarizing role. Marxism is a less extreme category in Ireland, and – somewhat surprisingly – corporatism has rightist connotations.

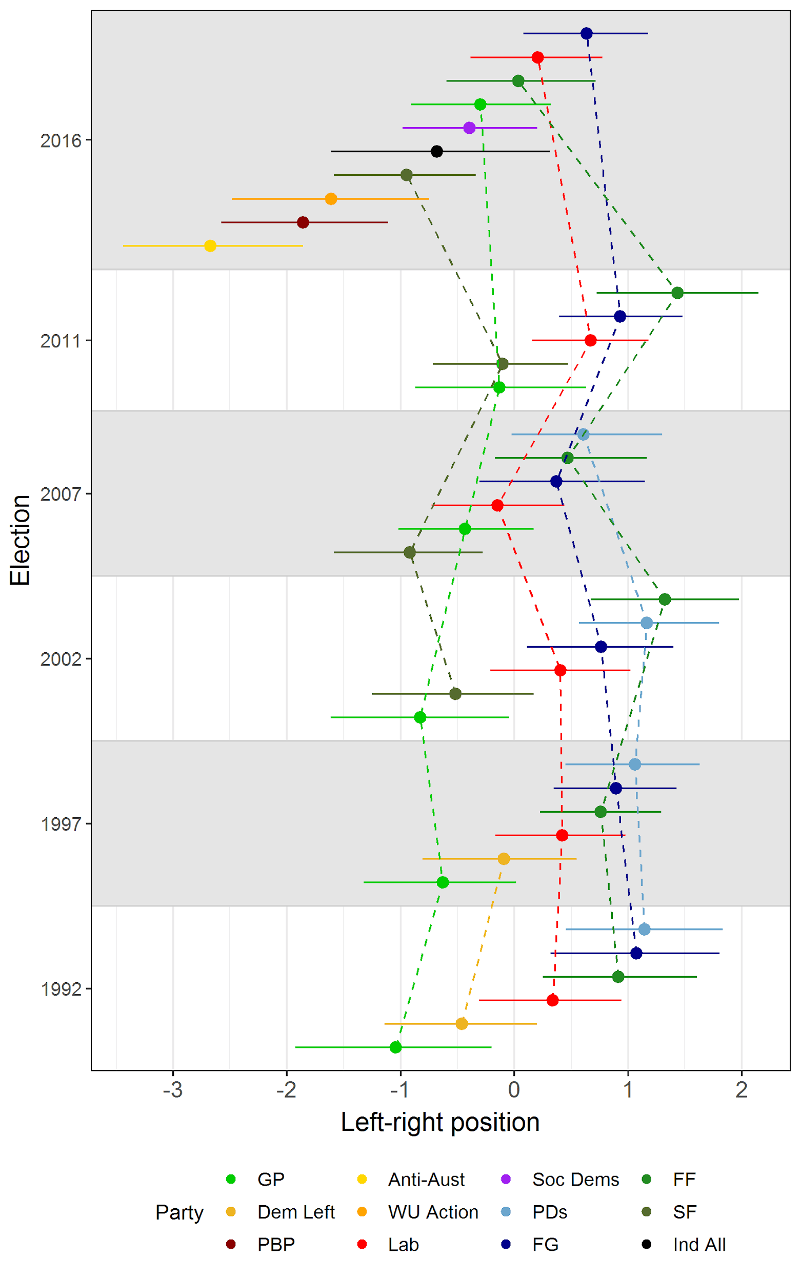

Figure 2: Party positions on the left-right dimension in Ireland, 1992-2016

Note: Shown are posterior means and 95% Bayesian confidence intervals. Positions of parties that appear in only one election before 2006 are not displayed.

Although the focus of this post (and the paper) lies on the content of left-right and thus on the policy categories, let’s also have a look at the inferred party positions (see Figure 2). I leave it to the reader to delve into whatever details are of most individual interest. Let me just point out two aspects of the most recent elections covered by the data (those of 2016) that seem noteworthy. First, there is evidence for a leftward shift of the overall party system, while levels of polarization increased in the sense that there are now several parties on the left with representation in the Dáil. Second, Fianna Fáil made a move to the centre in 2016, which – coincidentally or not – paralleled that of Sinn Féin. This move also implies that, unlike in the elections between 2002 and 2011, Fine Gael is now placed considerably to the right of Fianna Fáil. Last but not least, a word of caution is indicated. As Figure 2 also illustrates, any such conclusions are probabilistic in nature. Using nothing but the manifesto data and the scaling model, there remains considerable uncertainty associated with any such statements. It should be seen as an advantage of the model that it makes this fact transparent.

References

Däubler, Thomas and Kenneth Benoit. 2021. “Scaling Hand-coded Political Texts to Learn More about Left-Right Policy Content.” Party Politics (online first). doi: (opens in a new window)https://doi.org/10.1177/13540688211026076

About the author

Thomas Däubler is an Assistant Professor and Ad Astra Fellow in the School of Politics and International Relations at University College Dublin.