Sentiment & Emotions on Lebanese Politics

Authors: Luke Horton and Sofia Quaglia

Date: 9 November 2022

This blog post is the overview of a larger research project that seeks to determine if the Lebanese political actor Hezbollah tends to use higher levels of negative sentiment throughout public speeches than the Lebanese president. In parallel, this study touches on whether negative emotions, such as fear, appear more than positive emotions, such as trust, during and/or after pivotal events. To conduct such research, we scraped and cleaned a new Arabic data set from speeches published on official websites. We apply quantitative text analysis to perform sentiment analysis and extract the prevalence of specific emotions. The results were unexpected and countered what Western academics anticipated in their studies. Hezbollah prefers to use similar communication strategies as the President of Lebanon. Our study shows how text analysis can enhance our understanding of political conflicts.

Our research sets out to find how sentiments and (opens in a new window)emotions are used in conflict. We look at Hezbollah as a resistance actor and Michel Aoun, the president of Lebanon, as the establishment actor. A resistance actor is a political actor that is not in control of a sovereign state. Conversely, an establishment actor is the legitimate power holder of the said state. For this study, we look at Hezbollah, a particular resistance actor, and Shia militant group. Hezbollah is very involved in the country’s politics despite being recognized as a terrorist group by many Western powers. (opens in a new window)The political actor has 13 seats in the 128-seat Lebanese parliament. It is also considered to be a strong military power with more than 40,000 militia fighters in total.

First and foremost, it is necessary to understand what sentiment and emotions, or discrete emotions, are. A good theory to look at has been developed by Plutchik. (opens in a new window)They organize a system where 8 emotions contribute to either a positive or negative sentiment. Positive sentiment encapsulates 4 emotions: joy, trust, anticipation, and surprise. Negative sentiment covers the 4 other emotions including fear, anger, sadness, and disgust.

Since emotions impact behavior, or the way that we think and process things, it is expected that an appraisal of positive emotions will be connected to positive action, and vice-versa. Think, for example, about fear. When you feel afraid, you want to flee the situation at hand. When you think of trust, on the other hand, you think of something familiar and this can even bring you closer to the speaker. This is exactly what happens in political contexts. Political actors will use emotions to influence their followers. This ignites a certain reaction and manifests a political agenda.

In the context of the middle east, Hezbollah has been a longstanding resistance actor that has played an important role in shaping the region. You may have heard of Hezbollah in the news recently. Maybe you have heard of the (opens in a new window)Lebanese protests against ex-prime minister Saad Hariri that led to his resignation in January 2020 and the protests behind the incendiary Lebanese financial crisis. Or maybe you’ve heard of the (opens in a new window)Soleimani assassination and subsequent Beirut bombing in August 2020. Following this assassination, Hezbollah publicly announced its intentions to make the U.S. “pay the price” for its actions, highlighting its increasing aggression towards the Western powers. You may even recall the continuous (opens in a new window)clashes between Israel and Hezbollah, an explicitly anti-Zionist actor. This strenuous political tension has created even more pressure for both Israel and Muslim-centric political actors in the Middle East. As a result, Israel has been in a constant state of “deterrence”, whereas Hezbollah continues to quarrel with the state of Israel and tensions arise almost every year. These major events were referred to in specific public speeches on behalf of both the resistance and the establishment actors.

We collected speeches, both in Arabic and English, in order to create datasets we could work with. Using programming languages such as R, we were able to automate this process: a little robot collected speeches for us and organized them accordingly. Then, we used an Arabic dictionary to associate words with specific emotions and sentiments. This is the beginning of our sentiment analysis that helped us measure the frequency of positive and negative sentiment words followed by the frequency of discrete emotions words. Think of our “(opens in a new window)dictionary” here as a vending machine that separates coins automatically into different piles. This is the same principle for the dictionary that is able to categorize words into either positive or negative sentiment (or neutral!) and then into different discrete emotions. We focused specifically on the dichotomous emotions of fear and trust. We ran our sentiment analysis on both Aoun’s speeches and Hezbollah’s speeches and interpreted the results. Furthermore, we evaluated the presence of said sentiments and emotions after pivotal political events, such as the ones we talked about earlier.

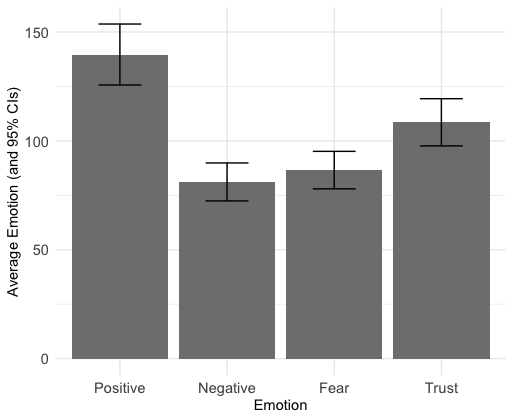

Figure 1: Average emotional expressions in Hezbollah speeches (with 95% confidence intervals)

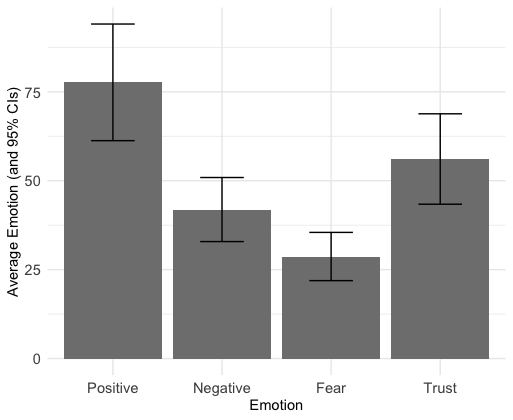

Figure 2: Average emotional expressions in Aoun speeches (with 95% confidence intervals)

The results were both surprising and relevant in the field of conflict politics. Our study shows that Hezbollah has a high prevalence of positive sentiment compared to negative sentiment. This is more than expected based on (opens in a new window)previous studies. In parallel, Hezbollah also shows high levels of trust, a strategy used to invoke ideas of stability and legitimacy in attempts to ground their supporters. Nevertheless, Hezbollah presents high frequencies of fear, especially when speaking about Israel. As a resistance actor, Hezbollah uses fear to present danger and other common enemies; this tactic is used almost as frequently as the discrete emotion of trust. As for the Lebanese government, Aoun has used positive sentiment (almost twice as much as negative sentiment) a lot throughout pivotal events. The establishment actor uses this as a communication tool and a strategy, especially when counterbalancing negative sentiment and fear which are byproducts of threats made against the sovereign nation. Similarly, Aoun uses trust significantly more than fear to convey feelings of national safety and security.

Some of the results above were anticipated for our study, yet some countered academic expectations. Such expectations were based on previous literature and studies on the subject matter. The baseline that emerges from the literature is that generally (opens in a new window)a resistance actor will show a prevalence of negative sentiment and fear in comparison to the establishment actor which would show high frequencies of positive sentiment and trust. The reason why our results are very interesting is because those that match our expectations see Hezbollah striving to fulfill the role of resistance actor. For example, the resistance actor will use more fear when faced with a strong sovereign establishment actor, such as Israel, to deter their own members from putting themselves at risk. However, when Hezbollah gives speeches after pivotal events, it mimics some of the strategies used by the establishment actor (such as using trust as a counterweight to fear) highlighting an important role in domestic politics. In addition, Hezbollah still surprised us when looking at the frequencies of positive sentiment. We believe that conducting more studies in Arabic, amongst other languages, will allow us to broaden our understanding of the relationship between emotions, sentiment, and conflict.

About the authors: Luke Horton and Sofia Quaglia are graduates of the MSc Politics and Data Science programme at University College Dublin. The blog post builds on a collaborative research paper submitted for the module “Connected_Politics”. The project was supervised by Dr Stephanie Dornschneider-Elkink.